This blog post is written by Lily Bui, M.S. Candidate in Comparative Media Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and it's cross-posted from the Tow Center for Digital Journalism blog.

Last July in Berlin, Lily Bui gave a session at the Open Knowledge Festival called Sensors, Uncensored. The session discussed different methods of using sensors to generate data in support of journalistic inquiry and public concerns. The attendees of this session organized a Google group to stay in touch, which has now culminated into a sensor journalism community of practice, which Lily discusses below. This groups is international and multidisciplinary, and they have recently collaborated on a pending Wikipedia article for sensor journalism.

As seen in the Tow Center's Sensors & Journalism report, the growing availability and affordability of low-cost, low-power sensor tools enables journalists and publics to collect and report on environmental data, irrespective of government agency agendas. The issues that sensor tools already help measure are manifold, i.e. noise levels, temperature, barometric pressure, water contaminants, air pollution, radiation, and more. When aligned with journalistic inquiry, sensors can serve as useful tools to generate data to contrast with existing environmental data or provide data where previously none existed. While there are certainly various types of sensor journalism projects with different objectives and outcomes, the extant case studies (as outlined in the Tow report) provide a framework to model forthcoming projects after.

But it may not be enough to simply identify examples of this work.

Invariably, just as important as building a framework for sensor journalism is building a community of practice for it, one that brings together key players to provide a space for asking critical questions, sharing best practices, and fomenting connections/collaborations. Journalism certainly doesn't happen in a vacuum; it is best served by collaborations with and connections to outside sources. A sensor journalism community has already begun to emerge on a grassroots level, spanning multiple countries, disciplines, and issues of concern. We might look to the nodes in this community to outline a protean map of stakeholders in the field:

Journalists.

Since public opinion can be driven by press coverage, and since storytelling is a central part of news, journalists, documentarians, and media makers with an interest in sensor data play an important role in shaping how the public perceives certain issues. More than that, the media also have the ability to highlight issues that may have slipped under the radar of policymakers. In this scenario sensor data could potentially serve as evidence for or against a policy decision. Most sensor journalism case studies so far have relied on normative forms (print, online) to convey the data and the story, but there is much room for experimentation, e.g. sensor-based documentary, radio, interactive documentary, data visualization, and more.

Educators.

In the classroom, there is an undeniable opportunity to cultivate a generation of journalists and media makers who are unintimidated by hardware and technology. Not only this — the classroom also becomes an ideal place to test technology without being beholden to the same restrictions or liabilities as professional newsrooms. Educators across the U.S. have begun incorporating DIY sensors into classroom projects (see Emerson College, Florida International University, and San Diego State University projects), the results of which touch on many of the same questions that professional journalists encounter when it comes to sensor tools. The teaching practices applied to sensor journalism can also be the foundations of training models for professional journalists and civic groups seeking to investigate issues.

Hardware developers.

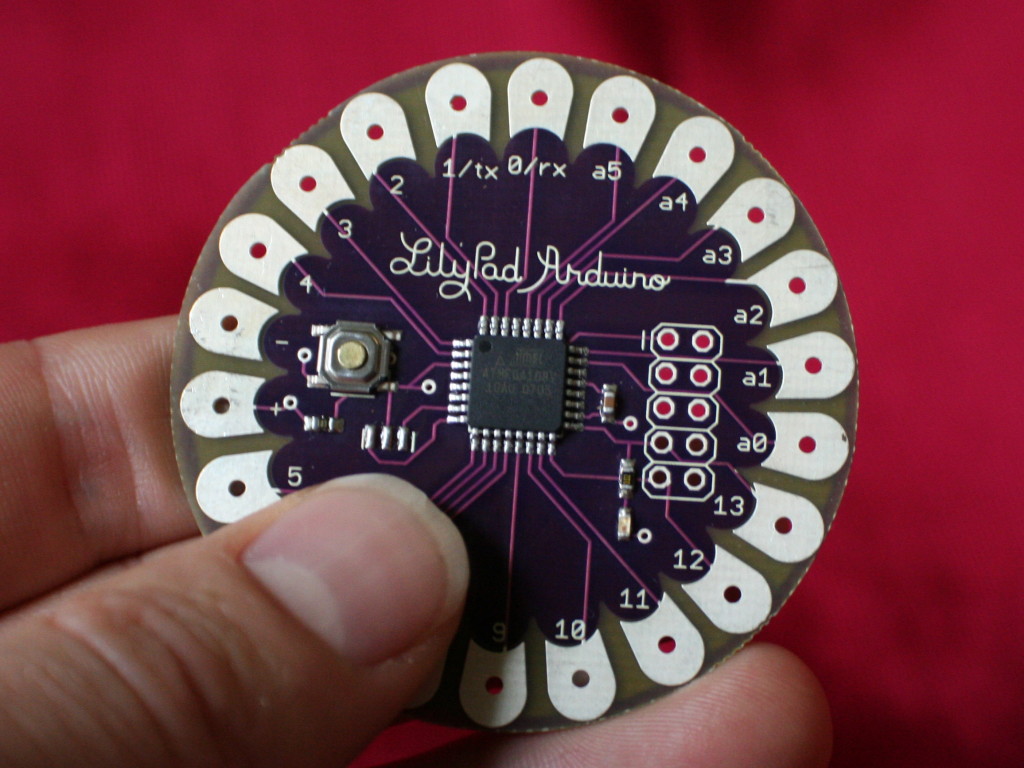

Because hardware developers design and build the tools that journalists and others would potentially be using, they have a stake in terms of how the tool performs downstream of development. Journalists can also collaborate with hardware developers in identifying tools that would be most helpful: Journalists may have specific requirements of data accuracy, data resolution, range of measurement, or the maturity of their equipment. Likewise, hardware experts can recommend tools that provide access to raw data and transparent interpretation algorithms. On the flip side, some hardware developers, particularly in the open source community, may help identify potential environmental issues of concern that then inform journalists' research. Recently, a conversation about certification of sensors, which originated within the hardware development community, crystallized around the notion of how to instantiate trust in open sensor tools (or sensors in general) when used for various purposes, journalism included.This is telling of how an open dialogue between hardware developers and journalists might be beneficial to defining these initial collaborative relationships.

Researchers.

Since using sensor tools and data in journalism is new, there is still significant research to be done around the effectiveness of such projects from both a scientific/technological standpoint as well as one of media engagement and impact. Researchers are also best poised, within academia, to examine tensions around data quality/accuracy, sensor calibration, collaborative models, etc. and help provide critical feedback on this new media practice.

Data scientists, statisticians.

Since most journalists aren't data scientists or statisticians by training, collaborations with data scientists and statisticians have been and should be explored to ensure quality analysis. While some sensor journalism projects are more illustrative and don’t rely heavily on data accuracy, others that aim to affect policy are more partial to such considerations. Journalists working with statisticians to qualify data could contribute toward more defensible statements and potentially policy decisions.

Activists, advocates.

Because many open sensor tools have been developed and deployed on the grassroots level, and because there is a need to address alternative sources of data (sources that are not proprietary and closed off to the public), activists play a key role in the sensor journalism landscape. Journalists can sometimes become aware of issues from concerned citizens (like the Sun Sentinel's “Above the Law” series about speeding cops); therefore, it’s essential to cultivate a space in which similarly concerned citizens can voice and discuss concerns that may need further investigation.

Urban designers, city planners, architects.

Many cities already have sensor networks embedded within them. Some of the data from these sensors are proprietary, but some data are publicly accessible. Urban designers, city planners, and architects look to data for context on how to design and build. For instance, the MIT SENSEable City Lab is a conglomerate of researchers who often look to sensor data to study the built environment. Sensor data about environmental factors or flow can help inform city design and planning decisions. Journalists or media makers can play a role in completing the feedback loop — communicating sensor data to the public as well as highlighting public opinions and reactions to city planning projects or initiatives.

Internet of Things.

Those working in the Internet of Things space approach sensor networks on a different level. IoT endeavors to build an infrastructure that includes sensors in almost everything so that devices can interact better with people and with each other. At the same time, IoT infrastructures are still in development and the field is just beginning to lay its groundwork in the public consciousness. Imagine motion sensors at the threshold of your house that signal to a network that you're home, which then turns on the devices that you most commonly use so that they’re ready for you. Now imagine that on on a neighborhood or city scale. Chicago’s Array of Things project aims to equip the city with environmental sensors that can report back data in real time, informing residents and the city government about various aspects of the city’s performance. What if journalists could have access to this data and serve as part of a feedback loop back to the public?

By no means is this a complete map of the sensor journalism community. One would hope that the network of interested parties in sensor journalism continues to expand and include others — within policy, legacy news organizations, and more — such that the discourse generated by it is a representative one that can both challenge and unite the field. Different methodologies of collecting data with sensors involve different forms of agency. In some sensor journalism scenarios, the agents are journalists; in others, the agents are members of the public; and in others yet, the agents can be governments or private companies. Ultimately, who collects the data affects data collection methods, analysis of the data, and accessibility of the data. No matter what tools are used — whether they are sensors or otherwise — the issues that journalists seek to examine and illuminate are ones that affect many, and on multiple dimensions (individual, local, national, global). If we are truly talking about solving world problems, then the conversation should not be limited to just a few. Instead, it will take an omnibus of talent and problem solving from various disciplines to pull it off.

References

Pitt, Sensors and Journalism, Tow Center for Digital Journalism, May 2014

Chicago's Array of Things project

Sun Sentinel's “Above the Law” series